Jon Regardie is a veteran Los Angeles journalist who has contributed to dozens of local and national publications, including L.A. Downtown News, where he served as editor, and Los Angeles Magazine, Blueprint, Westside Current and The Eastsider.

Everyone knows some version of the adage “cash is the lifeblood of electoral politics.” It’s why candidates hold fundraisers and spend endless hours “dialing for dollars.” The more money candidates have in their war chest, the more they can drop on getting their message out to voters through campaign consultants, mailers, lawn signs and social media marketing.

That’s why after the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission posts the 2025 fundraising totals for candidates running in the mayoral, City Council and other races on Jan. 31, a mini-news cycle will ensue: Some candidates will issue chest-thumping press releases touting a financial advantage over their competitors in the June 2 election. Journalists will parse the data for stories about who has the greatest haul and where it comes from.

But be careful of jumping to conclusions about what this means for the outcome of an election: The importance of money in political races is wildly overrated. In a surprising number of instances, cash is not king, and the concept that you can buy an election doesn’t hold true — in California, voters have shown an ability to see through the avalanche of dollars, time and again.

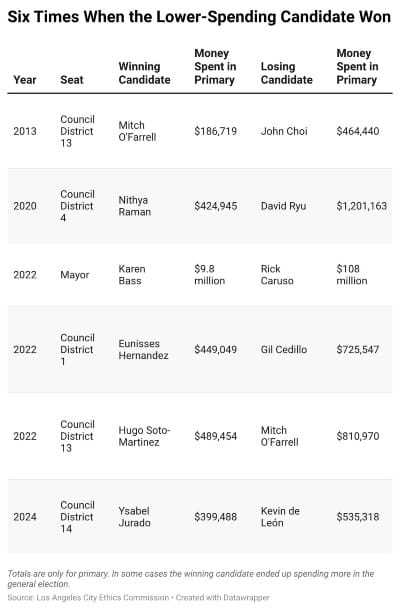

I’ve been covering L.A. city elections for a couple of decades, and while the better-funded figure wins more often than not, I’ve tracked numerous instances where the opposite happens. The most notable example occurred in 2022, when billionaire developer Rick Caruso’s campaign spent an astonishing $109 million in his bid for mayor, while Karen Bass’ campaign shelled out about $9.8 million. The 11:1 discrepancy didn’t matter — she won the November runoff by 10%, or about 90,000 votes.

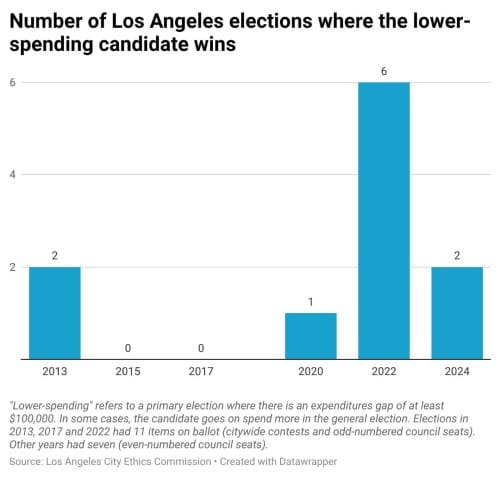

The attention lavished on Caruso’s geyser of expenditures masked something even more remarkable: Of the 11 races in the city that year, six were won by the candidates who spent less than their opponents — sometimes much less.

For example, in the city controller contest, Paul Koretz outspent Kenneth Mejia by nearly half a million dollars but got blasted. The trend continued down the ballot — in the city attorney’s race and in two City Council races where incumbents Mitch O’Farrell and Gil Cedillo significantly outspent their first-time opponents but still lost by a wide margin.

Golden State is a member-supported publication. No billionaires tell us what to do. If you enjoy what you're reading, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription and support independent, home-grown journalism.

This trend is neither new nor exclusive to local Los Angeles politics. In 1994, U.S. Rep. Michael Huffington, a Republican from Santa Barbara, spent $29 million — most of it his own money — trying to unseat Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein of San Francisco who spent $12.5 million; the race was close but Feinstein prevailed.

Four years later, airline executive Al Checchi tapped his personal fortune to spend almost $40 million in the California Democratic gubernatorial primary; that netted him 12.5% of the votes, each of which cost about $70. Gray Davis spent $9 million, equating to $5.92 per vote, and went on to become governor.

The most expensive miss in state history belongs to former eBay chief Meg Whitman, who in 2010 dropped $177 million — $144 million of it her own money — running for governor against Jerry Brown, who spent $36 million. Brown won by 13%.

Every big-budget electoral flop prompts extensive analysis of how someone can spend so much money for second place (or worse). No answer explains every result — sometimes the spending leads to over-saturation, especially in TV ads, that turns off voters. That might have been at play in Whitman’s loss, but so might her status as a Republican in a blue state competing against someone who had already been governor.

What do you think? Golden State is a public forum. Send us your responses for possible publication in the future.

Other times, a candidate just connects (or fails to) on a local level. In 2011, Warren Furutani boasted a political pedigree — he was in the state Assembly — and spent $426,000 in a special election primary for an L.A. City Council seat. He lost to Joe Buscaino, a San Pedro cop who spent $285,000 but had deep community ties.

Multiple factors contributed to Caruso’s 2022 loss. Voters may have tired of his incessant TV commercials or been turned off by the fact that he had once been a Republican and only registered as a Democrat shortly before launching his campaign. Add in the fact that Bass was a well-known member of Congress who had been on the short list to become Joe Biden’s running mate two years earlier, and one can question whether Caruso could have won at any spending level.

A more recent factor in city elections is the emergence of a progressive political movement whose candidates raised and spent less than competitors, but who managed to excite voters and connect with grassroots groups that can organize young supporters. In 2020, political rookie Nithya Raman spent $425,000 in the Council District 4 primary, or about one-third of what incumbent David Ryu dropped. She earned 41% and forced Ryu into a runoff, a result she later told me was helped by a 600-person “volunteer army” that knocked on 83,000 doors in the district. She won in the general election.

Councilmembers Hugo Soto-Martinez and Eunisses Hernandez benefitted from similar volunteer support when they were first elected in 2022, as did another left-leaning council candidate, Ysabel Jurado, in 2024. Three opponents outspent Jurado in the primary, but she reached the runoff, in which embattled incumbent Kevin de León again outspent her but still lost.

Each of the four progressives raised several hundred thousand dollars, so the fundraising and dialing for donations were certainly essential. They also all benefitted from an additional six-figure check from the city’s matching funds program.

But money is not the only thing that determines an election. A candidate doesn’t need to have the most funds to spend, but they do need enough to run their race. And if they can connect with the electorate on another level, they can win.